GreenWave’s 3D Ocean Farming Program

I’d like to introduce Patagonia’s friends and customers to the work of GreenWave, if you don’t already know it. GreenWave and its 3D ocean farming program have received much attention lately from the national press, including The New Yorker, CNN and NPR. Bren Smith, founder and executive director of GreenWave, gave a TED talk that has garnered nearly 30,000 views on YouTube. Last fall, GreenWave won the 2015 Fuller Challenge, a $100,000 prize awarded each year for an innovative, ecologically sensitive systems approach to a critical problem. How to feed ten billion people by 2050, without turning the planet into desert, is as critical as a problem gets. GreenWave, a small organization, has come up with an approach that can put food on a lot of tables—and help revive the economic health of maritime communities decimated by fisheries collapse.

Bren Smith, as a commercial fisherman, made his own contribution to that collapse. Raised in Newfoundland by American parents who emigrated to Canada during the Vietnam War, he dropped out of school at fourteen to go to work at sea. His first job was to stand on deck and shoot as many birds—competition for bait—as he could. He lobstered off the coast of Massachusetts, longlined for McDonald’s in the Bering Sea and slimed in the canneries of Bristol Bay. His environmental education involved, as it has for most of us who work at Patagonia, a gradual burn-off of the stage fog through which we see the human-imposed impoverishment of the natural world. It helped Bren that he could see it up so close. Finally, having become an oysterman in the Thimble Islands of Long Island Sound, he saw his crop wiped out two years in a row by the force of Hurricanes Irene and Katrina. It was then that he decided that to make a sustainable living from the sea he needed to, in Doug Tompkins’s words, move forward by taking a step back.

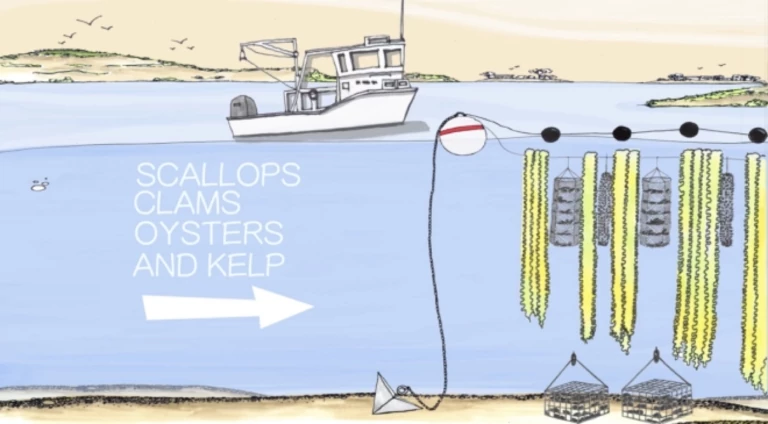

An illustration of 3D ocean farming: hurricane-proof anchors on the edges, horizontal floating ropes across the surface with kelp growing vertically down next to scallops and mussels, with oysters in cages and clams buried in the sea floor. Illustration: Stephanie Stroud

The beauty of 3D farming is its simplicity: Grow as many different foods in as small an area as possible, along droplines suspended by buoys, using the entire water column from surface to bottom. Bren works the same stretch of waters off New Haven where he once cultivated oysters. Oysters are still part of the harvest, as are mussels, clams and scallops that grow like companion plants along the droplines. But the star is sugar kelp, which is prolific, that sprouts along the lines: it can grow as much as three-quarters of an inch a day. Kelp needs no special inputs. It absorbs nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon dioxide directly from the sea—and is an extraordinarily effective carbon sink. Kelp can be used as an organic liquid fertilizer, a biofuel, food for sheep and cattle (that reduces their methane output) a binder for food (ice cream, for example) and for centuries has served as nutritious food in itself for Asian cultures. Leading chefs and food researchers in New York, the Hudson Valley, and the Bay Area are now trying new uses of kelp, including as noodles, to satisfy newly aware western palates.

Sugar kelp on the line at Thimble Island Ocean Farm. Courtesy of Edible Nutmeg #29, Summer 2016. Photo: Jan Witting

There are other potential benefits: the farm serves as a reef for local fishlife and the gear as surge protection in local storms. 3D farming is a relatively simple, noncapital-intensive business to get into.

No human economic activity, as yet, is without environmental cost—as long as boats run on gasoline. And our understanding of how regenerative ecosystems might work in harbors long used for commercial activity is nascent. Scientists from Woods Hole and U Conn are deeply involved in GreenWave’s work. The fisheries biologists we know will be watching it closely. GreenWave’s approach feels to me like a good step in the direction conservationist Aldo Leopold’s advised us to take, that “a thing is right when it tends to support the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community,” one that includes human beings. We are now tasked with restoring to nature as much as we take from her or lose our own place in the sun. GreenWave’s work offers a model for how that might be done.

Learn more about GreenWave at greenwave.org. There are a variety of ways you can get involved: learn how to be an ocean farmer, become a research or chef fellow, and contribute to their fall fundraising campaign.