What’s at Stake Is the Future of Humankind

Yvon Chouinard shares how our company continues to do what it can to defend the soil, air and water we all depend on—and to confront the greatest threat to our welfare we’ve ever faced.

This story was first published on March 14, 2019.

“Forget Mars,” Yvon Chouinard said—although, come to think of it, he might have used a stronger f-word. Our founder was responding to a glib idea that comes up from time to time in conversations about the climate crisis—that if we exhaust the Earth as a habitat for humans, we’ll all just up and move to the red planet. Chouinard, and Patagonia, would rather not, and are more determined than ever to save our home planet. In an interview for Patagonia’s 2018 Environmental and Social Initiatives book, Chouinard shared how our company continues to do what it can to defend the soil, air and water we all depend on—and to confront the greatest threat to our welfare we’ve ever faced.

When the total of Patagonia grants to grassroots organizations topped $100 million, it seemed like there was a reluctance to go public with that, maybe because the company has never been one to boast about its numbers.

Yvon Chouinard: Oh, I’m not reluctant at all. I think we should be proud of that because it demonstrates what a company can do, and not just what its shareholders can do once they’ve collected on their investment and decided how to give away some of the proceeds. Our grants were given as we conducted business.

Patagonia continues to give directly to activists. As the company has grown, have you considered changing that?

We always thought the activists were the ones who needed the money most. There’s plenty of funding for science, but science without activism is dead science. And activists struggle to get funding because everybody’s afraid they’ll do something radical. Companies, especially, see them as risky, and not worth the trouble. So we thought: Let somebody else do the science. Let somebody else do large-scale conservation projects. We’ll fund the activists. And that’s what we’ve done.

If anything has changed, it’s that we’ve started producing movies like DamNation. We could have given money to international organizations that work on dams, but I felt like we could do a better job if we made a movie ourselves. And that proved to be true: DamNation wasn’t another environmental film that went nowhere. It really got around.

I’ve always said that all of us, in our own way, according to what resources we have, must do something to confront evil. At Patagonia, we have all these resources—we have better marketing expertise than most any environmental organization out there—and yet we were giving money away to other people to do the marketing on issues we care about. Why not use more of our own expertise? That’s what got us into the film business. We’re a film company now.

I really want us to face up to the fact that we’re destroying the planet. It could very well end up uninhabitable in 80 years, at least for humankind and wild animals. That’s why we recently changed the company’s mission statement to “We’re in business to save our home planet.”

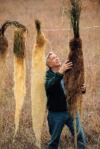

A cousin of annual wheat, Kernza thrives without tilling, which helps prevent erosion. Once the grain is harvested, the roots remain in the soil, holding carbon underground as they break down. Photo: Jim Richardson

That’s it, then, “We’re in business to save our home planet”?

Simple as that. I’m 80 now, and I’ve been asking myself why I still come into work. And it’s not to sell more clothes or to make more money. It’s because we’re destroying the planet, and it’s gotten so dire that we have to do something. When you talk to new people at our company, you’ll find that this is why they come here, too: because they’re committed to saving the planet.

Aside from hiring those who feel the same urgency, how do you see the company further embracing this commitment?

We’ve come to the conclusion that the best thing we can possibly do is support regenerative agriculture. I don’t know of anything else that can really solve global warming. Sure, we could try to stop using fossil fuels. Good luck with that. Good luck with going against Exxon and all those big energy companies. We’d end up spending a lot of money doing effectively nothing if we tried to take them on. Instead, what we’re learning about capturing carbon with agriculture is encouraging. See, with organic agriculture, you remove all the harmful chemicals, but that’s about it. With regenerative agriculture, you’re able to grow more nutritious, better-tasting food; you’re growing topsoil; and you’re capturing carbon—so it’s a way of farming that’s a win-win-win-win situation. I see it as a real positive solution. It’s our best hope.

Regenerative ag practices building soil and capturing carbon in a cotton field in India. Photo: Tim Davis

Patagonia’s adopted a pair of progressive benchmarks for cleaning up its own act. One was becoming a B Corp in 2011. Has that been worthwhile?

Yes. It hasn’t caught on as much as I’d hoped, but it does provide a framework. We’ve heard from other businesses that it’s helped them, too. When we started looking into a lot of this, there weren’t many places to go for help. Now there are some pretty good ones.

What about the Higg Index, which the company uses to assess social and environmental issues in the supply chain?

The index helps us stay on track, but I’m disappointed that bigger companies haven’t done more. When we started down that road in 2007, everyone was talking about “sustainability,” and now that word is basically meaningless.

Wild Idea buffalo battle climate change on the Great Plains. Photo: Jill O’Brien

Given how daunting the climate crisis is, it’s going to take lots of different actors to change course, including the government. Do you see Patagonia working more with the government to save the planet?

We can’t rely on this government. The current administration is evil. All they want to do is destroy the planet for profit. You’re not going to change their minds. You’ll just beat your head against a wall. You know, I don’t make a very good martyr. I really think we just have to get them out of there.

As a company we’re going to spend more on political policy, but for me it’s a waste of money compared to what we could be doing on the causes, instead of the symptoms, of global warming. We’re also committed to cleaning up our own act and have already begun to make the changes necessary so that by 2025 we will eliminate, capture or otherwise offset all of the carbon emissions we create. This includes not just our offices or stores, but all of the emissions from the factories that make our textiles and finished clothing and farms that grow our natural fibers. Eventually, we want to remove more carbon from the air than we put out.

When we first started giving money away, we knew that we were doing harm to the planet, but we didn’t know that we were totally destroying the planet—and destroying it very, very quickly. What I really want to get across is that we’re in an all-hands-on-deck type of situation. What’s at stake is not only the future of some endangered species or large mammals; it’s the future of humankind. And it’s gonna happen within people’s lifetimes. It’s a whole different scenario now. So let’s get on it.

This is an abridged version of the interview. For the full conversation, see our 2018 Environmental and Social Initiatives book.